In the beginning what used to be called black tea by the West was actually oolong. I have explained that in my reference tea site in this article: Black Tea: Origin & Production, so I won’t repeat myself here.

The production processing of traditional oolongs is still very demanding on both skills and labour today even with aid of semi-automatic machines. It was imaginably more so back in those days.

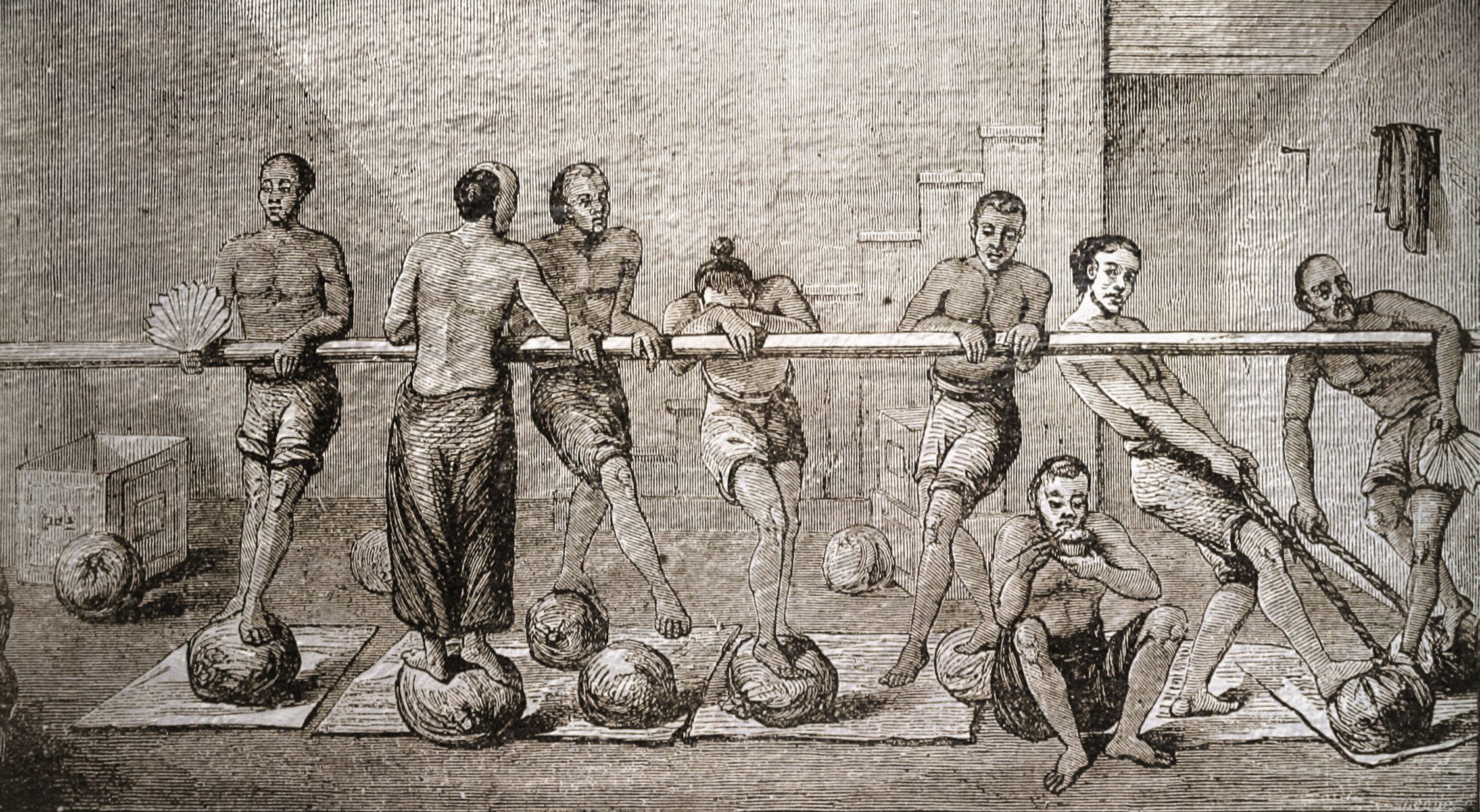

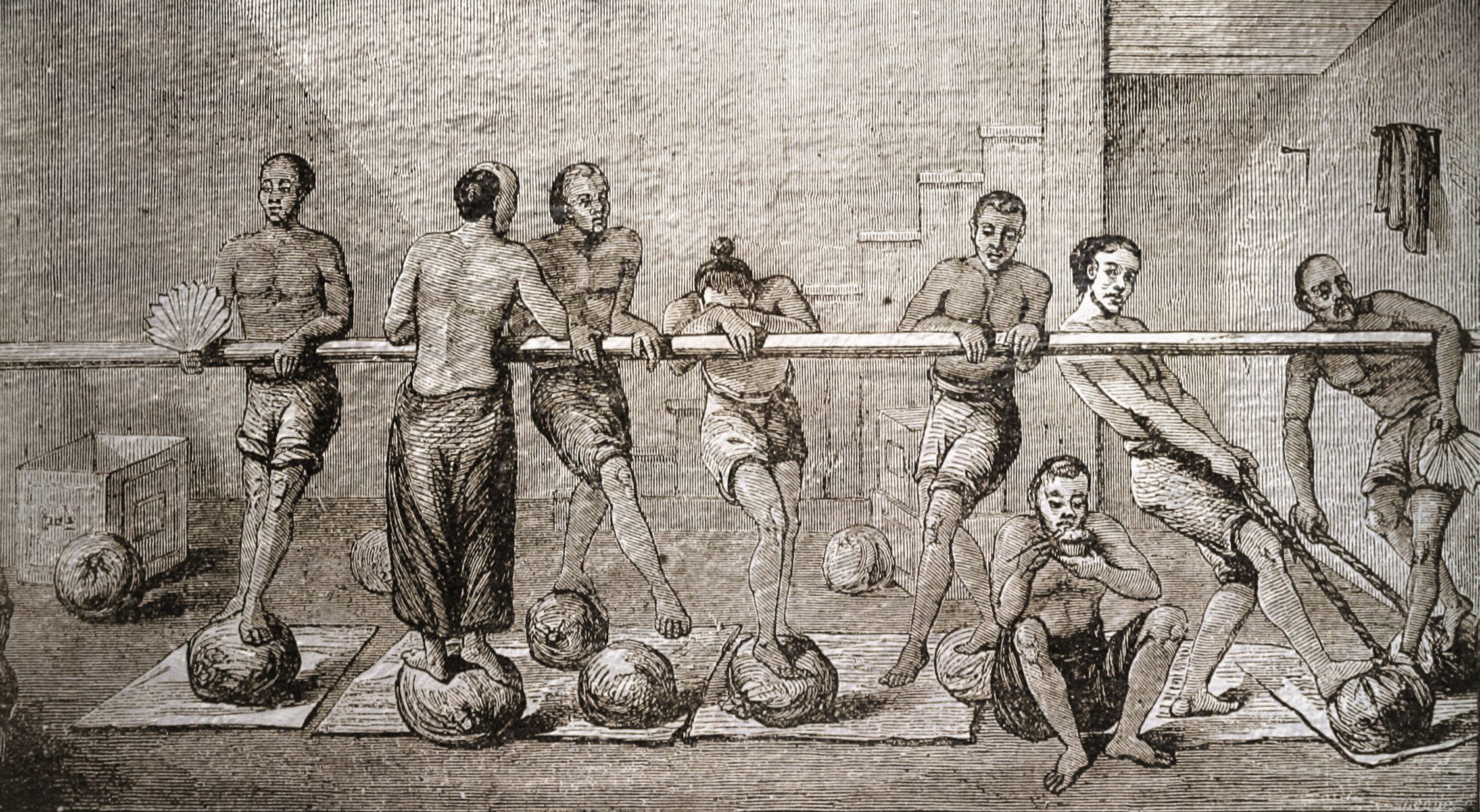

Tea being rolled by turning the volume under the foot, probably late 1800’s.. This used to be the most popular way of rolling the leaves, especially during the final stages of rolling. I am old enough to have witnessed this being done by an 82 years-old tea master in the late 1990’s. He said that it used to be a few rounds of rolling by hand on the bamboo, but this would not be tight enough, so the last rolling step would be rolling by foot. He was doing it just to show me how he did it in his younger age. Notice that the leaves are wrapped by a cloth into a ball as they are nowadays in the production of certain teas, though not by foot.

Although the invention of black tea in the 18th century had a primary aim to save a portion of work and material limitations ( as discussed in the article ), different producers still had the pressure of producing higher quality in a competitive market. The amount of skills and work ( gongfu per se ) to make the beautiful and tightly rolled, soot black strips of dry leaf was still very demanding.

A gongfu black tea literally means a black tea that is produced with skills and efforts.

It is not known which production area or which tea variety in particular first came up with the name gongfu black tea, but the label “congou” (i.e. gongfu)* first appeared in an English printed page:

London Gazette issue 6376, 25 May 1725, page 2, Advertisements,

“Next Week will be sold, a large Parcel of Bohee**, with some Congou and Green Tea…”

Sadly the label “Congou” has been gradually misrepresented in the West with ever lowering quality that what you see inside the tea canister with that name hardly represents the traditional quality at all. I was quite completely shocked when I toured one of those very famous and prestigious teashops in London and showed a can of it. That was in 2003.

Master Li turns the leaf pile to aerate the leaves during a lengthy withering process. Red Jade production, Yu Chi, Taiwan. The leaves are withered for long hours in the manner of traditional gongfu black tea processing during which they have to be periodically and gently loosened up and reshuffled to ensure evenness in temperature and withering before rolling for oxidation.

Genuine gongfu black teas, such as Keemun, Red Jade, Red Plum, Tongmuguan, Lapsang Souchong, etc are still alive and in good demand nowadays thanks largely to a bourgeoning tea followers in the Far East and a growing awareness of quality in the West. They are still inappropriately represented in big brands though.

Gongfu black tea in production term actually refers to a more rigorous process than regular black tea. Not only does it require more time and skills, but also more in-between steps, including a few more operations in delicate rolling of the leaves and intermediate resting. Finesse of the process differs from regions to regions, variety to variety and even producer to producer, all basing in the grand tradition that has been passed down since the 18th century, but fine-tuned and developed locally in villages, each according to better understanding of the science behind and development of specific tea cultivars. Because of the manual nature of the process, timing and vigour of each step can be fine-tuned to the unique conditions of each harvest. The weather — which affects both the growth and pluck conditions of the leaves and the conditions of the processing environment — is a huge variant in the quality equation. This is a far cry from the automation in mass market black tea production. Although new machines and modern technologies have already been in place in many farms, it is still the production master that the key to a fine cup of gongfu black tea.

Automatic mist spray from above in the oxidation chamber. Red Jade production, Nantou, Taiwan. Humidity control during the long hours of oxidation ( fermentation ) of the tealeaves is key to the gastronomic quality of the product.

The “gongfu way of preparing and drinking tea”, on the other hand, is independent and unrelated to the name of this branch of black tea. So next time when you want to enjoy a cup of gongfu black tea, such as our great value Ying Hong Nine, feel free to steep it in the infusion style you prefer, whether in a mug, in a teapot, or even in a small gaiwan or zisha teapot in the gongfu style. Just make it well to let the gongfu behind the production of this fine tea manifest itself through a satisfying taste experience.

Enjoy!

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

Notes

*In the early years of tea export, many terms were transliteration from various southern Chinese dialects. It was the southern provinces, such as Fujian and Guangdong that the export ports were situated. One example is the very word tea itself. The Chinese word for tea — 茶 — is pronounced as thé, or té, depending on whether you are nearer Chaozhou (the gongfu tea capital of the world), the key skilled labourer source, or if your nearer Shantou (historically represented as Amoy), one of the export ports in early 18th century. It was this dialectical representation that has been transformed into the many forms of the word tea in the West. Do not forget there were also various dialectical manifestations of the original term in different Southeastern Asian populations, where some of the early sailors and tea merchants came from.

Similarly, the original term for gongfu — 工夫 — is spoken as gang-bo, kang-hu, or kung-fu, depending on who you speak to. Congou is a rough combined form of transliteration.

** The term Bohee, or more frequently Bohea, refers to what is transliterated as Wuyi today, i.e. teas from the Wuyi Mountains, likely referring to Wuyi oolongs or similar teas made in Anxi or other neighbouring regions (see details in the Tea Guardian article that I wrote, as mentioned earlier). Again, Bohea is an ancient and rough transliteration from a southern dialect, likely one from Minnan.

Comments (0)

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.