Why do they steep Longjing in the glass?

Every single client I have ever travelled with to Hangzhou has asked: why do they all steep Longjing in the glass?

Contrary to popular practice, the full profile of Longjing is not obtainable by infusing the tea in a glass.

The shortcomings to most are obvious: difficult to drink from a glass when it is so hot, and the leaves will be all over the lips and mouth if you dare the scalding heat. The glass is also a clumsy vessel to pour from, if you want to decant the tea into smaller cups.

To me the other critical concern is that tea does not infuse well in a drinking glass without a lid. It is difficult for anyone to taste the full taste profile of any tea when it is simply soaked in a glass.

A habit done by most people does not necessarily mean that it is a good habit. It is actually more so for many things in China, including practices in tea drinking. The billion people living within the national boundary of dictatorial rule have many things in their way of life needing to reconstruct from a full century of cultural annihilation. Maybe three centuries come to think of it.

Tea is an easy starting point, so let’s all do the right thing to influence back on them.

Tea is better when infused with a lid

Generally, a Longjing infusion comes out far better from the teapot or gaiwan. Like any other teas.

The drinking glass is a poor infusion vessel. Bad convection within the liquid body, too much heat lost through the large surface area, and all the obvious inconveniences for handling a hot liquid. A lidless vessel also means undesirable drop of temperature on the surface. Combining this with poor convection, your leaves are very evenly infused. Not to mention the escape of all the evaporative essential oils. Don’t forget such aromatic matters are key to the taste profile of a tea.

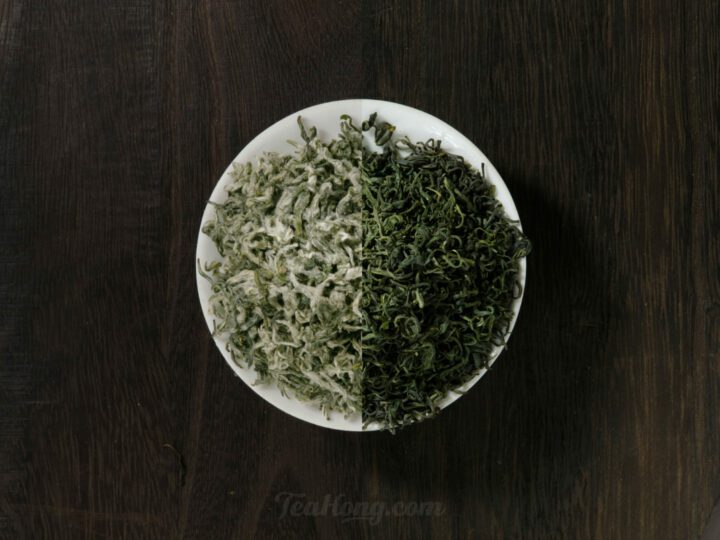

In the beginning, people used the convenient transparency to showcase the evenness and tenderness of the young plucks. Not for drinking.

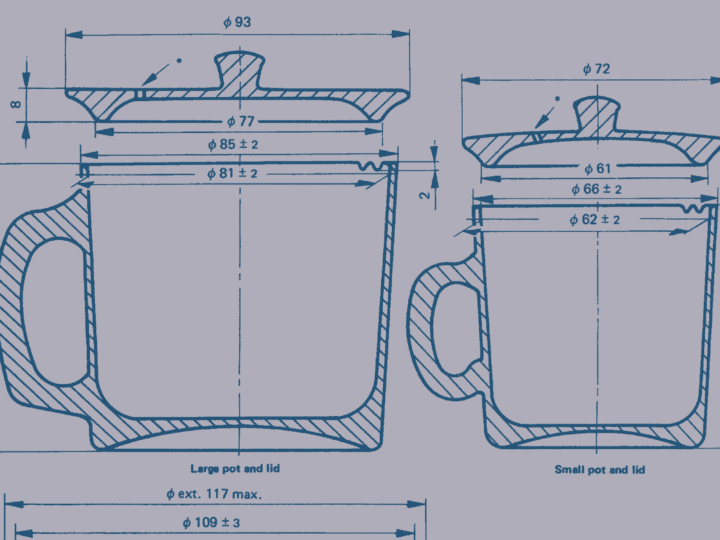

As I have explained in articles in the Tea Guardian, both the gaiwan and the teapot are good infusion vessels when they are sensibly designed and made. Properly used, they deliver a good representation of almost any tea.

If you want more infusion tips than in the product page for steeping Longjing Spring Equinox, here are some hints:

Season your Yixing pot

It takes more skills to use a Yixing teapot to get the best of a Longjing. To begin with, it has to be very well and properly seasoned. The reward is more, however.

Teapot vs gaiwan

The teapot gives better rendering of the umami aspect, while it is much easier using the gaiwan to experience the aroma.

Double the leaves, a third the time

If you choose the gaiwan, one way to enjoy better aroma is to increase the leaves and lessen the time for infusion. Begin with doubling the quantity and a third the duration. Adjust from there to your personal liking and play with it for understanding the tea. However, as with any tea, shortened infusion time draws a different ratio of the taste matters in each subsequent round. You will be experiencing the tea in a stage-progressive manner.

Thinner infusion vessel, shorter time

If you are using a thin vessel, adjust the leaf quantity so you don’t have to use long infusion time like 5 minutes. Use a very slightly higher temperature for that too, like 87°C.

For me, it is always 2g to the 100ml water for smaller vessels and smaller cups. And much longer infusion time. I like a Longjing infusion dense and strong and full of flavours. It is my expresso of green tea.

Once you have got the hang of it, you will understand the fine taste of ancient China a lot better, totally worth the civility of proper teaware and the handling I preach, unlike whatever you might have seen in those teashops in the land they also call China today.