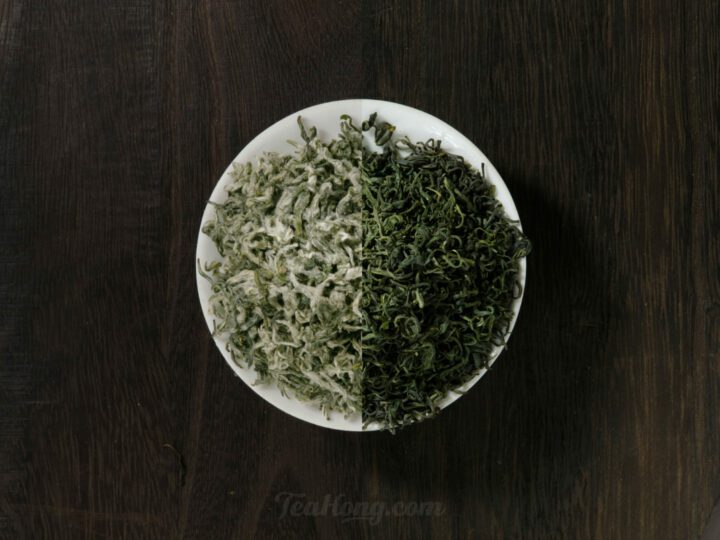

This pluck is almost big enough for producing Taiping Houkui. The leaves of the Shidaye cultivar is by far the biggest in size for green tea production

Shidaye — the largest leaf bud for green tea

The huge leaf buds clearly showed their size difference 50 meters away, under the setting sun. I was telling my client from Belgium that they still needed some time to grow. Mr An, our producer in Anhui, picked a one shoot two leaves sample that was almost the length of his palm. “This is the size we are waiting for,” he yelled. It is the biggest leaf bud for tea ever. ( See slideshow below )

The only cultivar for Taiping Houkui

Taiping Houkui is produced from this special cultivar called Shidaye ( shi-da-yeh ). The name can be roughly translated as Persimmon Large Leaf. ( It has nothing to do with the fruit, though. ) It is the most visible commercial crop in the hilly landscape of Taiping, an hour and a half from Huangshan. Unlike most other green teas, which premium crops are harvested much earlier in the year around the Spring Equinox, the leaves of Shidaye gain size and taste through most of April before selectively hand picked. It is by far the largest size green tea.

The making of traditional quality

When we arrived at their home at sunset, old Master Wang’s whole family had been working since five in the morning picking the leaves and processing them. The leaves softened in the firewood wok were twisted and pinched onto a wire mesh in a square frame. Hence the name of this class of Taiping Houkui — Nie Jian, i.e. Pinched Tippy Leaf Shoots. This is the traditional way.

We all tried our hands on doing what seemed to be the simplest part, twisting the leaves to lay on the mesh. Only the lady in our small tour group was able to do the job well enough to be tolerated to stay on.

Pressed and then baked

The leaves in the frame were then passed through a roller press to be flattened. Like all other green teas, heat is applied to the leaves to dry them. It is very much the manner in which the leaves receive this external energy that transform their innate biochemistry into the final taste quality. In the case of Taiping Houkui Traditional, they are slided into a wooden oven for baking.

Fire: the real deal

The real deal of the whole processing is mastering of the fire. Master Wang is basically a chef of tealeaves in that sense. The key ingredient that makes the difference is the charcoal that fuel the baking in the wooden drawer-chest oven. Master Wang has what he said his ancestral secret way of making the charcoal. His special charcoal kiln, which anyone would have missed as being a mound of dirt, could be how it would have been a millennium ago, when odourless charcoal was the fuel of choice for all tea connoisseurs.

Charcoal that makes the difference

The precious charcoal needs to be pre-fired in a pan underneath the oven so that when the first mesh frame of the day is pushed into the wooden drawer chest, there is no visible fire and no burning smoke, just glowing charcoal ash.

One could argue that an electric oven would take care of all these, like what they do in other quality grades of greener looking Houkui that are made in the modern way. Yet for some reason, most premium teas in China are still being processed using this same ancient fuel. I cannot put my finger on the taste difference, but somehow there is a special warmth and roundness in a charcoal baked tea that is not present in others.

From dawn to dusk

When we finished the dinner prepared by Mrs Wang it was half past ten, unusually late in rural China. The last mesh frame had not entered the oven until an hour ago. The whole family needed to finish processing all the picks that day. The two week of harvest is the major avenue of income for the whole family for the year. It was a peak day and they had made almost 8 kilograms. As Mr An put the sack of Taiping Houkui Traditional at the back of the small SUV before driving us back to Huangshan, I knew the product was at least two days of work from the family.

Who is there to carry on a back-breaking tradition

Old Master Wang grabbed my hand tightly to ask me to visit again. He was probably too proud to say please continue to buy from him. Or that he was too artistic to care about business. What flashed across my mind, however, was a little more sinister. Who would be able to continue his craft after he passed away? There seemed to be a lot yet for the son-in-law and the daughters to learn, as I have seen during the evening’s stay. Finding a quality maker in the hundreds of small family tea farms in the area is a taunting task. I really do not hope to go through this again.